Many months ago, we had explored the differences between various members of the AK family (e.g.) AK-47, AKM, AK-74, AK-101 etc. In today's post, we will explore some of the popular members of the M16 family and discuss the differences between them. We will study the differences in multiple posts, as there are quite a few variants with major differences.

M16: This is the first operational version of the rifle and was only adopted by the US Air Force initially. Among its distinctive features are a triangular shaped forward hand guard, no cleaning compartment in the stock (as Colt famously declared that this rifle was so advanced that it didn't need one), no forward assist lever and a duckbill shaped flash suppressor at the muzzle. The original version was issued with a 20 round magazine. It is capable of selecting firing modes and can fire in single-shot as well as fully automatic modes. The barrel has a rifling twist of 1 turn in 12 inches.

In the above image, we see an original M16 rifle. This variant was adopted by the US Air Force, which continued to use this model until 2001 before switching to the M16A2 variant. It was also used by some other military forces, notably the British SAS.

M16A1: This is the variant that was first accepted by the US Army. Soon after the original M16 was ordered by the US Air Force, the Army got in the act and asked for a model with a few changes to it, notably, the addition of a forward assist lever, in case the cartridge did not properly seat in the chamber. Colt and the US Air Force believed that this change was unnecessary, over-complicated the weapon and increased its cost by $4.50. Hence, the Air Force got the M16 variant and the Army got the M16A1 variant., which has the forward assist lever. One more difference is that the duckbill flash suppressor was found to pick up twigs and leaves in jungle conditions and was replaced by a bird-cage style flash suppressor. This variant retains the same triangular forward hand guards, selectable firing modes (single-shot and fully automatic) and rifling twist of the original M16.

Early versions of the M16A1 were issued with no cleaning kits and without a chrome lined chamber. This led to a number of jamming issues early on and investigations were made to determine why this was happening. A change in the ammunition formula was found to be the cause, as the new ammunition left more residue in the rifle. Since the rifle was issued without a cleaning kit, soldiers could not properly maintain their weapons and this led to jamming problems in the field. Immediately after the cause was determined, the rifle was changed to include a cleaning kit, stored in a compartment in the stock. The barrel. bolt and chamber were also chromed to resist corrosion. In 1970, the magazine was changed from 20 round capacity to a 30 round capacity, as can be seen in the image above.

After its initial reliability problems were solved, the M16A1 variant became adopted by the US Army and the Marines, as well as other military forces around the world, such as Argentina, Australia, Thailand etc. It is still used by some military forces.

M16A2: This is a very influential version of the M16 family and has a number of differences from the M16A1. Most of the changes were added because of the US Marines. The Marines found that in the Vietnam war, many inexperienced men would put the rifle into fully automatic mode and end up emptying their magazines into the bushes without hitting a single enemy. Hence, they asked for the automatic firing mode to be removed and a three-round burst mode to be added instead. This makes the M16A2 variant capable of firing in single-shot and three round bursts only. Also, NATO forces wanted to use a more powerful version of the 5.56x45 mm. cartridge (the SS109 cartridge). However, the newer cartridge needed the rifling twist of the barrel to be changed, in order to maintain bullet stability in the air. Hence, the M16A2 features a barrel with a twist rate of 1 turn in 7 inches (compared to 1 turn in 12 inches for the earlier models) to work with NATO standard cartridges. The barrel thickness was also increased as the US Marines wanted a stronger barrel to resist bending in the field and not overheat as quickly.

There are also many other major changes. For instance, the material of the buttstock plastic is different and 10 times stronger than the original. The shape of the forward hand guards is round instead of triangular and the two handguard pieces are symmetrical (meaning that either half can fit as the left or right side hand guard). This enables the rifle to be held more easily by smaller hands and the symmetrical hand guards make production easier, as there is no longer a need to manufacture separate left-side and right-side hand guards. The shape of the pistol grip is also different - this version has a notch added to support the middle finger and it has more texture to enhance the grip. Because this rifle is designed to fire the NATO SS109 cartridge, the rear sights are also changed to match this new cartridge's ballistics. Also, the flash suppressor is modified and closed at the bottom, so that it will not kick up dust or snow when fired from the prone position.

This variant was initially adopted by the US Marines and then by the US Army, followed by the other branches of the US military and other military forces around the world. It is still being used by many military forces around the world.

M16A3: This is a variant of the M16A2 model that came out at around the same time as the M16A2. It was produced in small quantities and designed for US Navy SEALS and the Seabee units. The main difference is that while the M16A2 can only fire in single-shot and three-round bursts, the M16A3 can fire in single-shot and fully automatic modes. Special forces are trained to not waste ammunition and hence, this variant allows fully automatic fire.

In the next post, we will study some more variants of the M16 family.

M16: This is the first operational version of the rifle and was only adopted by the US Air Force initially. Among its distinctive features are a triangular shaped forward hand guard, no cleaning compartment in the stock (as Colt famously declared that this rifle was so advanced that it didn't need one), no forward assist lever and a duckbill shaped flash suppressor at the muzzle. The original version was issued with a 20 round magazine. It is capable of selecting firing modes and can fire in single-shot as well as fully automatic modes. The barrel has a rifling twist of 1 turn in 12 inches.

Original M16 rifle. Click on image to enlarge. Public domain image.

In the above image, we see an original M16 rifle. This variant was adopted by the US Air Force, which continued to use this model until 2001 before switching to the M16A2 variant. It was also used by some other military forces, notably the British SAS.

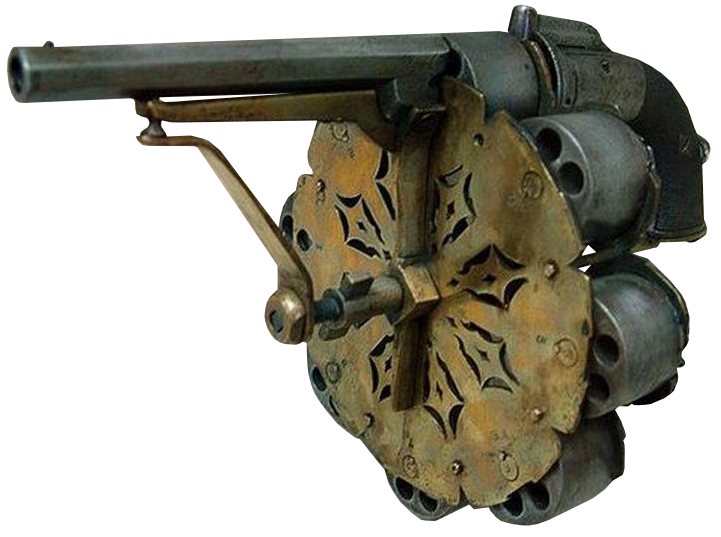

M16A1: This is the variant that was first accepted by the US Army. Soon after the original M16 was ordered by the US Air Force, the Army got in the act and asked for a model with a few changes to it, notably, the addition of a forward assist lever, in case the cartridge did not properly seat in the chamber. Colt and the US Air Force believed that this change was unnecessary, over-complicated the weapon and increased its cost by $4.50. Hence, the Air Force got the M16 variant and the Army got the M16A1 variant., which has the forward assist lever. One more difference is that the duckbill flash suppressor was found to pick up twigs and leaves in jungle conditions and was replaced by a bird-cage style flash suppressor. This variant retains the same triangular forward hand guards, selectable firing modes (single-shot and fully automatic) and rifling twist of the original M16.

The M16A1 rifle. Note the bird-cage flash hider in front of the muzzle and the presence of a forward assist lever.

Early versions of the M16A1 were issued with no cleaning kits and without a chrome lined chamber. This led to a number of jamming issues early on and investigations were made to determine why this was happening. A change in the ammunition formula was found to be the cause, as the new ammunition left more residue in the rifle. Since the rifle was issued without a cleaning kit, soldiers could not properly maintain their weapons and this led to jamming problems in the field. Immediately after the cause was determined, the rifle was changed to include a cleaning kit, stored in a compartment in the stock. The barrel. bolt and chamber were also chromed to resist corrosion. In 1970, the magazine was changed from 20 round capacity to a 30 round capacity, as can be seen in the image above.

After its initial reliability problems were solved, the M16A1 variant became adopted by the US Army and the Marines, as well as other military forces around the world, such as Argentina, Australia, Thailand etc. It is still used by some military forces.

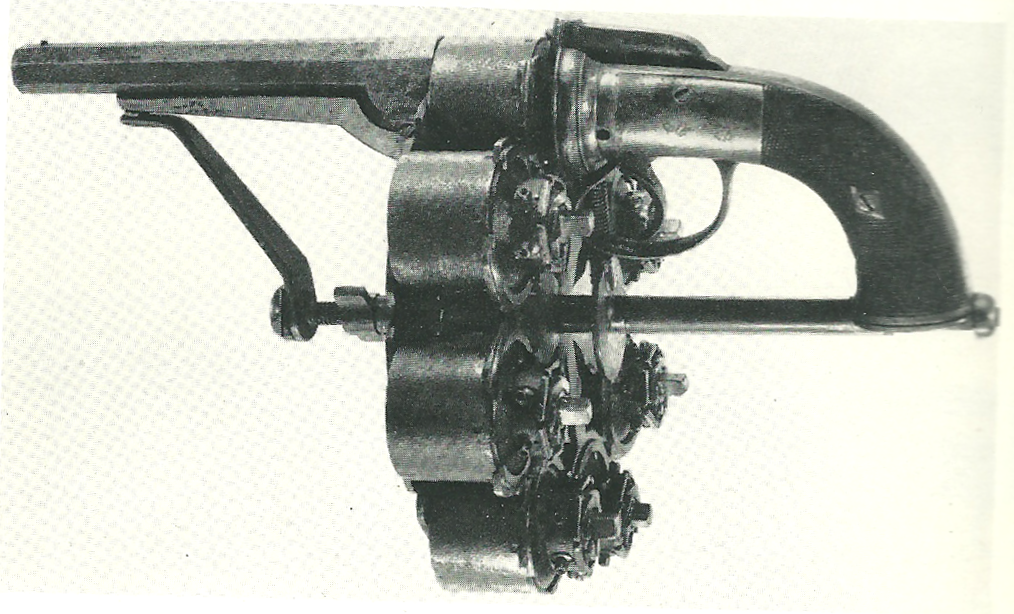

M16A2: This is a very influential version of the M16 family and has a number of differences from the M16A1. Most of the changes were added because of the US Marines. The Marines found that in the Vietnam war, many inexperienced men would put the rifle into fully automatic mode and end up emptying their magazines into the bushes without hitting a single enemy. Hence, they asked for the automatic firing mode to be removed and a three-round burst mode to be added instead. This makes the M16A2 variant capable of firing in single-shot and three round bursts only. Also, NATO forces wanted to use a more powerful version of the 5.56x45 mm. cartridge (the SS109 cartridge). However, the newer cartridge needed the rifling twist of the barrel to be changed, in order to maintain bullet stability in the air. Hence, the M16A2 features a barrel with a twist rate of 1 turn in 7 inches (compared to 1 turn in 12 inches for the earlier models) to work with NATO standard cartridges. The barrel thickness was also increased as the US Marines wanted a stronger barrel to resist bending in the field and not overheat as quickly.

The M16A2 rifle. Click on image to enlarge. Public domain image.

There are also many other major changes. For instance, the material of the buttstock plastic is different and 10 times stronger than the original. The shape of the forward hand guards is round instead of triangular and the two handguard pieces are symmetrical (meaning that either half can fit as the left or right side hand guard). This enables the rifle to be held more easily by smaller hands and the symmetrical hand guards make production easier, as there is no longer a need to manufacture separate left-side and right-side hand guards. The shape of the pistol grip is also different - this version has a notch added to support the middle finger and it has more texture to enhance the grip. Because this rifle is designed to fire the NATO SS109 cartridge, the rear sights are also changed to match this new cartridge's ballistics. Also, the flash suppressor is modified and closed at the bottom, so that it will not kick up dust or snow when fired from the prone position.

This variant was initially adopted by the US Marines and then by the US Army, followed by the other branches of the US military and other military forces around the world. It is still being used by many military forces around the world.

M16A3: This is a variant of the M16A2 model that came out at around the same time as the M16A2. It was produced in small quantities and designed for US Navy SEALS and the Seabee units. The main difference is that while the M16A2 can only fire in single-shot and three-round bursts, the M16A3 can fire in single-shot and fully automatic modes. Special forces are trained to not waste ammunition and hence, this variant allows fully automatic fire.

In the next post, we will study some more variants of the M16 family.